Global maritime domain awareness and vessel analysis

ReleasesLearn about our latest improvements

Arming research analysts with hidden clues to their maritime domain

Global maritime domain awareness and vessel analysis

ReleasesLearn about our latest improvements

Arming research analysts with hidden clues to their maritime domain

Maritime domain awareness starts with an awareness about the people doing the work

Q&A · 22 November 2022 · 10 minute read

Starboard’s Chief Product Officer discusses how to build software to manage maritime environments sustainably

Ask Andy Hovey to design you a software solution and you probably won’t get what you ask for.

In fact, he’s unlikely to talk with you about the solution you have in mind at all. Instead, he’ll ask you what you do. He’ll delve into the details of your day; who do you talk with, how you share information with them, why are you doing it at all?

As Chief Product Officer for Starboard Maritime Intelligence, Andy spends his days making tools that help people manage maritime environments sustainably. It’s a macro challenge that Andy tackles by first understanding the people doing the work. Anyone who’s worked with Andy in this way has appreciated that genuine interest he takes in the why and the how.

Because although the Starboard Maritime Intelligence platform solves some key challenges for people working in the maritime space, it’s the collaboration Andy and his team bring to the work that his users rave about.

We managed to turn the tables on Andy and sit him down to find out what his days at Starboard Maritime Intelligence look like, why he does what he does and what possibilities he sees for Starboard. Spoiler alert, Andy reckons with Starboard, he can help people better understand the maritime world by focusing on the vessels that matter–allowing them to manage their maritime domain resources sustainably.

| Q. How did you get involved with Starboard Maritime Intelligence? |

A. My background is actually in design, I studied it and after I left Design School I started working in digital straight away. I cut my teeth making CD ROMs – remember those! – and websites for the education sector. It was a great starting place to introduce me to the world of software design. After a decade or so, I was in the lucky position to take a bit of time off and I spent nearly three years travelling around the world’s greater mountain ranges in South America, Central Asia, India and Nepal on a bike. When you do that sort of thing, you get time to have all these grandiose thoughts about life and what to do with it. I thought ‘well, doing something to do with health would be really cool, and something to do with the Earth would be really cool’, so when I came back to New Zealand I started thinking more seriously about those things; the Earth and health.

A friend of mine was working at Xerra Earth Observation Institute and invited me in to have a chat about what they were up to. They had this very smart and inspiring team working on Earth Observation, which is something I hadn’t thought of before but I was drawn to it because it fitted perfectly with my idea of working with the Earth, using it respectfully and having a healthy relationship with it. |

| Q. What is it you love about designing software? |

A. I don’t think about designing software, I think about designing tools people can use to do their thing. I like to learn about what people do, it’s a natural inclination I guess for me to take interest in the day-to-day. When someone says ‘I’m a fireman’ I think ‘what does that actually mean?’ You wake up, you start your day…and then what happens? I wonder ‘how do you get to work, who do you work with, how do you work with them, how do you feel about that, why are you doing that work?’. All of that sort of stuff is, I think, quite interesting. When you’re making software tools it’s still about understanding people. To build something that helps people do their job, makes them more effective, makes them a bit faster, you need to understand what they do more broadly. It’s not about the cliche ‘what do you want?’, because people don’t often know what they really need.This was definitely true in designing out the Starboard platform, because I listened to what our clients wanted and when we delivered these tools that solved their needs, they were surprised as it turned out way better than what they had been expecting. Over the last few years at Starboard I have learned so much about the maritime domain. That’s one of the best things about working in software, you’re making things for people so your expertise is the software and thinking about how people use it, and making it easy for them, but to apply that so it’s useful, you end up soaking up a tremendous amount of insight about the industry. My most recent job before Starboard was at Xero so naturally I absorbed a lot about accounting. It just works its way in and then there’s a point when you’re at a party and someone says an accounting joke and you laugh… |

| Q. How did you take that approach into designing for Starboard? |

A. I guess I was in a really fortunate position when I joined Starboard because there wasn’t a set plan. What we had was this really awesome team, some funding in this broad area of Earth Observation and a desire to do something good for Aotearoa. I came in, I looked at all the players on the field and thought ‘I wonder what we should do?’ We had already done some bespoke work with the NZ Ministry for Primary Industries so that was a good starting place. I did a lot of reading about the maritime industry and Earth Observation in general. Of course I chatted to a few folks as well. I looked at all that, discussed our direction lots with the team, and thought ‘well, we’re in the Pacific, there’s a lot of water, lots of things happen far away from land, satellites are quite good at looking at things far away from land, there’s a lot of data science complexity and we have those skills on our team’. I’m a big believer, from a software perspective, that first off, you need to solve one problem or a couple of problems for a small group of people better than anyone else. Then you can expand. So we gathered together about 50 people across seven different government agencies and created a kind of beta programme of work.I started out by just calling people up asking ‘what do you do and how does this work, how does this information get to someone else, how do you do this, how do you do that?’. You might think that people find that intrusive, asking very detailed questions about their day, but actually most people like talking about what they do. A lot of people, especially in government jobs, do things that aren’t well understood. So when someone wants to learn about their job and says ‘we’ve got an hour, talk me through what you do’, they usually love it. I think it’s the same for all software tools–you’re trying to understand a person’s broader goal and then the tasks that make that up. But understanding how they feel is really important too, it gives you a sense of where to focus your product and experience but also about solving their pain points. |

| Q. Is culture important to good software design? |

A. Yes totally. And I think you start building that culture by first finding out what makes people happy and what success looks like. In my experience, a successful team is one that is happy, one that works really closely, frequently ‘ships’ software and that the people who use it are also happy. All of those things more or less go together and what is nice about our team at Starboard is we’ve created this environment where we design and build in a highly iterative and highly collaborative way. We sort of have a philosophy of ‘build the dumb version’ which basically means we get something to the browser and App as quickly as possible, so we can all experience it as a user would. That includes the output of a model or whatever the data science is. We’ll prototype the data just like we’ll prototype the interaction. Having the chance to experience it as a user makes all the difference. The thing is, to me, user experience is not a job in itself. User experience is determined by the entire culmination of a company, from the investment approach that it takes, to the philosophy it has to engineering, the passion of the leadership to the policies it operates within.That all has such a huge bearing on the experience of the person using your service. |

| Q. What’s your secret to making Starboard such an easy-to-use tool? |

A. We are fortunate to have all those things I mentioned inbuilt to our culture. With our excellent technical team and great technical leadership there’s been a clear mission to build infrastructure, technical tooling and approaches that allow us to deliver frequently. We’re constantly pushing to production, like multiple times a day. It’s usually just small code changes but that keeps us moving and improving. That makes technical infrastructure so important to our work–everyone in the team can do their bit and do their best but they’re also operating in a framework that allows them to get that stuff into the world, safely. And from an excitement and cultural perspective, constantly making those small improvements is really important.

I think we’ve managed to build a great culture, working with a highly iterative and collaborative process. It means if we say ‘we’re going to have to change it’, people go ‘yeah! That’s going to make it better!’, not ‘oh, I thought I was done with it’. I think it’s also incredibly important for the people building stuff to meet the people using the stuff. We’ve just done a series of interviews with customers about map annotation, and one of our front-end devs, Nick, came along to every interview to hear what people do and chat with them. That’s cool, to be able to connect people, because in the end they want a thing and we’ve got people here who can make that happen. To quote Jared Spool, an industry expert UX Designer, the number one item on the path to improvement is to get your engineering team to watch the people that use the tool. Because if they have any heart, they’ll want to make it better. |

| Q. The maritime sector is complex. How do you create simplicity amongst that complexity? |

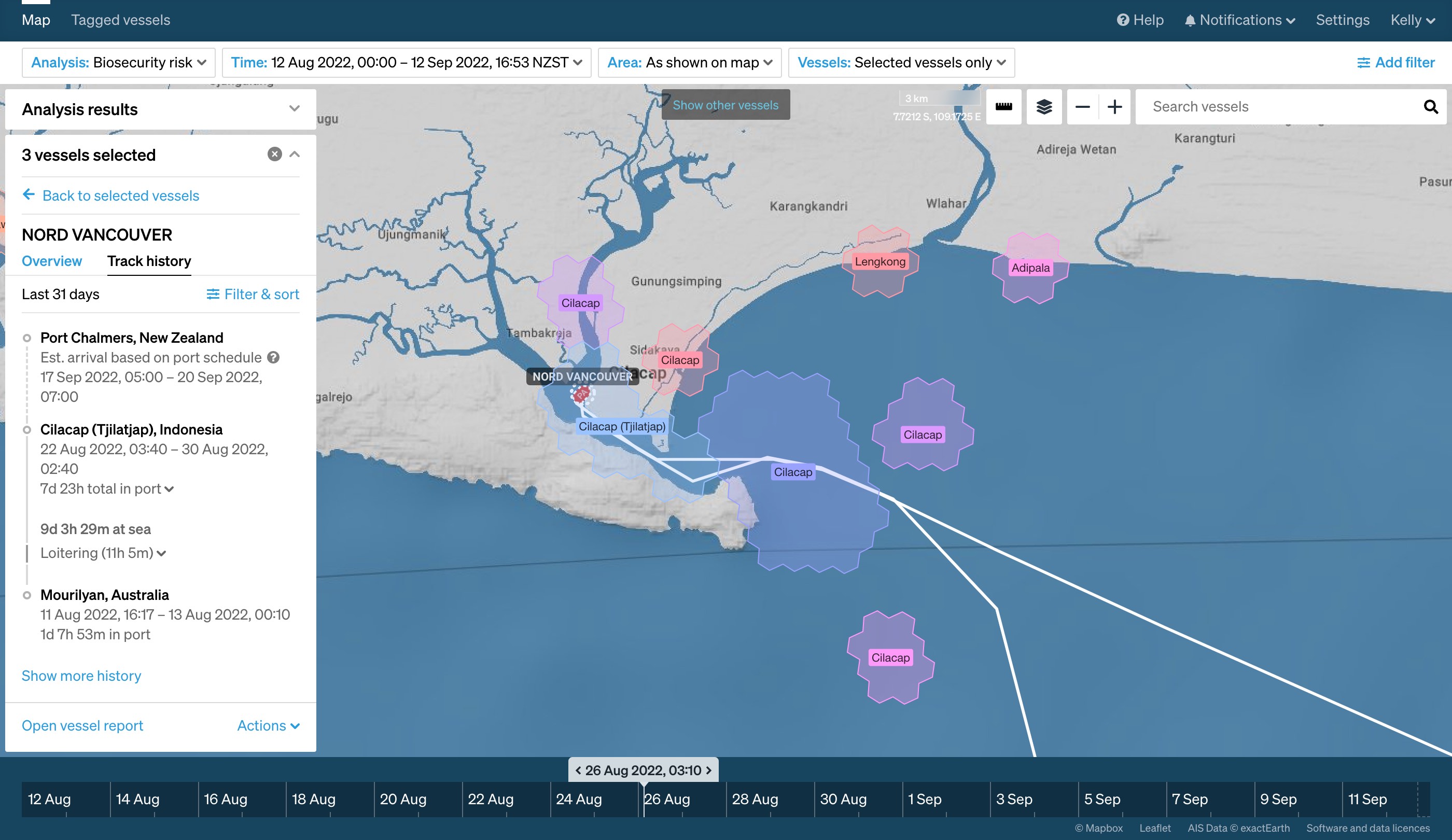

A. It is an incredibly complex space. For customs and border security it’s about ensuring the things that come into your country are compliant and safe. For biosecurity, it’s about ensuring that the vessels and the cargo don’t bring in any bad bugs that threaten your nation’s environment. Then for fisheries, it’s about ensuring sustainable use of resources. In all of those cases there is a very complex interplay between many players. From our perspective at Starboard, there is a commonality in the information that all of these sectors need–an ability to understand a vessel. To do that, you need to know where it’s been, who it’s met with, is there anything unusual about it and then, be able to make a judgement on that. Alongside that is comparing other information that’s been gathered about the vessel as well self-reported information like arrival documentation. For our customers working in the maritime space, we divided their problems into ‘In Office’ and ‘At Sea’ problems. We made the call early on that learning about those In Office problems is important, but our speciality is to focus on the At Sea problems and find a way to link solutions to those as seamlessly as possible into the working environment. That can, and has, had a halo effect in solving some of the In Office problems at the same time. For At Sea problems, we asked ‘what are our customers trying to ask about the world, what are they trying to find out about vessels?’With that question you look at things from a global perspective and you realise that ports matter and particular aspects of ports matter, as well as aspects of meeting other people.  Starboard’s global port database is critical for defining a vessel’s lay-up in ports. Here the NORD VANCOUVER has spent nearly 8 days inside the Cilacap port boundary in Indonesia. This event means it has been automatically flagged as a risk for carrying foot-and-mouth disease.To get to that point, you need to be really focused, uncovering how people share information to do their jobs to achieve their goals–whether it’s writing reports, understanding and measuring policy effectiveness or keeping things moving safely. One thing we uncovered was that a lot of screenshots were being emailed back and forth. Everything they’re looking at needs to be shared with someone else. So we wrote a simple URL solution that lets you copy and paste exactly what you’re looking at, like a specific vessel’s journey, and share it with whoever else needs to be across it. It’s simple but so effective. That’s basically what we do–try to make it easy to extract the information you need. |

| Q. What are the possibilities that you can see for Starboard? |

A. I look at the future for Starboard from two angles. From an outcome perspective I think that across the Pacific, thinking about the changing geopolitical landscape and the impacts of climate change on them, we can support and help improve the understanding of the maritime domain across the whole region. We can enable better collaboration and support across nations, we can help decrease some of the factors that impact the region, like illegal fishing, improve biosecurity by reducing the spread of invasive species, and overall help nations better understand their domain and manage their resources long term. From a software perspective, I think that even though we’re a small group of people, growing fast, in time we can make the best maritime domain awareness platform in the world. That may come from a place of naivety or arrogance, or even a blend of both but I really can see that. Because there’s a combination of information about the maritime world, plus the data science to process it, plus customer information, plus the platform we’re building that is going to enable people to answer these very complex questions they have about their maritime domain. To monitor it effectively and be given useful information about which vessel is interesting and why, as well what they need to do next. I think we’ve got a solid foundation now and the next stage will be incredibly exciting. |

Get a demo

Learn more about Starboard for fisheries analysis and investigations.

Read more

CUSTOMER CASE STUDY

Flagging vessels with heightened risks, such as foot and mouth disease, supports the planning and processes for border teams

Read case study →

CUSTOMER CASE STUDY

Sabina Goldaracena is a custodian of the South West Atlantic maritime domain. She connects the clues in her investigations, uncovers hidden activity and works towards transparency by sharing her stories.

Read case study →